|

I did some work over here but as always I can't recommend anyone read it. I mean, sure, go ahead, but it's all sorts of broken. The new changes are an attempt to fix that.

0 Comments

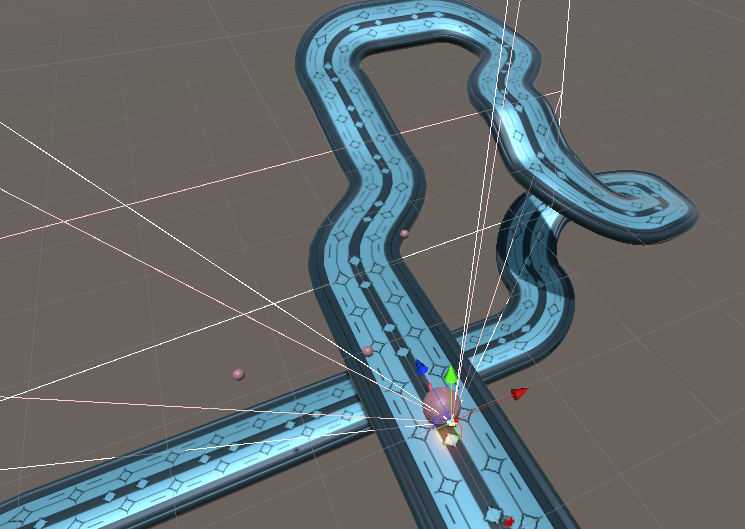

This screenshot is the beginning of at least the next year. I'm making a game. It's a roll'a'round, demolition derby, beat'em'up with a heavy metal soul. Wish me luck.

Best Games - Worms 2

In the early 1970s, computers were wildly expensive machines that occupied entire rooms of universities and research centers. Students and scientists would have to book time on them to do their work, often accessing them remotely from terminals. They would have to master early high level programming languages and think in trigonometric functions. With such specialized training and access to rare and costly hardware, they did what anyone would have done. They made and played games. One of the earliest tasks for electro-mechanical and electronic computers was calculating firing arcs for long range ship cannons. When computers advanced from relays to transistors to integrated circuits, the desire for the navies, armies, and air forces of the world to figure out how to shoot at what they are shooting at didn’t go away. If anything, shooting at things rose to the level of complexity afforded by newer computers. Shooting at things became a science. If it seems like a lot of computer games are simply about things shooting at other things, it might be because that was quite literally what computers were made for. Like it or not, performing ballistic calculations is built into computers from the bones out. In the late 1960s and early 1970s there was a pervasive shift toward antiwar sentiment in the research centers and universities of north america. And yet they were using computers. Computers for which ballistic arcs and missile flight dynamics were essentially solved problems. A lot of the basic languages included functions to define these arcs. The tools were all there, but the want to use them for their intended purpose was not. So people did what people will always do. They made a game out of them. Artillery isn’t really a single computer game. There isn’t one monolithic work that you can point to and say ‘that is Artillery’. Instead, artillery was an entire genre of computer games back in a time when genres for computer games didn’t really exist. Two or more gun emplacements would take turns firing at each other. Players would have to adjust the guns power and angle for each shot gradually trying to narrow in on their target. First one hit loses. Everyone programming a computer could play with and modify a version of Artillery. There were ones with changing wind, ones with variable terrain, ones where the gun emplacements could move and ones where they were ships on the sea. All of them variations on the same game. Sometimes it isn’t the game that explores a mechanic first that is remembered. Sometimes it isn’t even a game explores that mechanic best. Sometimes it is a game that just does it the most. Worms 2 is the most Artillery game ever made. Now of course, there was a Worms game before Worms 2, but it was really just Artillery in a comedy suit. Worms 2 though, they put everything in there. Every Worm had a goofy name and a slate of ridiculous voice samples for all situations. The amount of tools and weapons at your disposal is staggering, and most of them are bad puns and corny jokes. In 1997, nearly 30 years of Artillery style games were rolled into a single chuckle-worthy package. There have been a lot of Worms games since Worms 2, but not many have captured the joyous chaos of that game. Like using a sword to cut a cake or high explosives to create vibrant fireworks, Worms 2 took the core concepts of Artillery and repurposed them to entertain. What had been developed essentially as a weapon was transformed into whoopee cushions and cartoon googly eyes. Worms 2 is the most perfect form of the Artillery genre, and a crowning achievement in irreverence. Worms 2 is also one of the best games. I attended the RebootDevelop Red game development conference this past week. Somewhere, tucked away in the back of my memory, is the last time I ever attended a game development related conference. When I was there I witnessed a spirited demonstration of Samba De Amigo, a maraca based rhythm game. I also tried out a version of the real time translation functionality in Phantasy Star Online. If you know either of these two games, you know that it has been quite a long time since I was at a game development convention. According to people I talked to who had attended conferences like GDC and PAX, RebootDevelop is not the usual fare.

I could write stories about who I saw, what we did, and conversations that I had, but I would really rather not. There is a reason why I number rather than title all of these posts. I have a strong belief that that some experiences should be ephemeral. Some moments need not be recorded. I realize that all of these posts are searchable and discoverable, but I don’t really make it easy. Maybe for the internet that is ephemeral enough. Here is what I will say. I don’t know if I have ever been more convinced that what I am trying to do, making games, is the only thing I should be doing. It’s not that I couldn’t do other things. I certainly spent a long enough time in the various branches of advertising. If I needed to I could probably create store displays, commercials, and promotional banners again. But that isn’t what I should be doing. I should be making games. Every person I talked with, every person I had even a brief interaction with while at lunch or refilling coffee or ordering my third beer for the night, every single one of them was working in games because if they didn’t, no one else would. The long and short of it is, making games is incredibly hard. It’s technically, artistically, economically, and emotionally hard. Everyone I met had skills that could take them far in other industries. They could all be wildly successful doing anything easier than making games. But they weren’t doing other things, because they couldn’t do other things. At some point during the three day conference I was in the middle of a conversation with a game developer and I realized something. The game they were telling me about the game they were proud of, and had put so much of their effort and passion into, if they hadn’t worked on it, no one would have. That game would simply have never existed without that one person’s dedication. The thing was, it was a very good game. It needed to exist. The world is a better place because that game exists. And without that one person, that game would not ‘be’. There are games that I want to see in the world. There are games that I think need to exist. The only thing stopping them is that I haven’t made them yet. I need to change that. |

Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Owen McManus

RSS Feed

RSS Feed