|

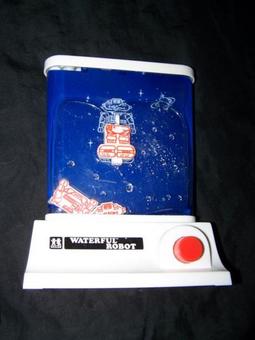

When I was a kid someone got me the Wonderful Waterful Robot. It was one of those water filled toys with a single button attached to a simple water pump. Press the button, and you squeeze water out of the pump reservoir and into the main chamber like a fully enclosed squirt gun. The movement of the water would float the 4 robot puzzle pieces around inside the chamber. The swirling was so chaotic that the toy appears to be just a random tempest of plastic objects. I loved it. The object was to float the robot parts up and onto a plastic guide in the center of the playfield. To win you had to not only stack the parts in the proper order, but also in the correct orientation. The guide had a graduated width so that only the feet could fit in the foot position of the puzzle. This meant that if you just wanted to stack all the parts on the guide, there was only one possible order. No putting the pants above the head monkey business. Wonderful Waterful Robot was here to challenge you and it has no time for silliness. That became crystal clear when you finally went to put the head on the top. The head piece has no hole for the guide to fit into, and the guide stops just before the neck. If you want to put the head on and finish the puzzle you would need to gently float it up on top without shooting the water out so hard that you push the torso up and off the guide. It was almost cruelly difficult. I was probably 4 years old, and I must have completed that puzzle dozens of times.

Here is the thing about the Wonderful Waterful Robot. Anyone who picked it up was compelled to mash that button way past the point of simply getting it. An adult who picks up a child's toy can usually figure out the boundaries of the experience fairly quickly, then they lose interest and put it back down. A child will play with anything, because every experience is novel to a 4 year old. An adult might take a bit more convincing. So why then did this dumb, random, kids robot puzzle keep everyone who attempted it hooked longer than a ball and cup. I think I have the answer to that, and it has something to do with the nature of fun. Okay so you will have to forgive my pedantry for a minute here while I break this down. I both despise and participate wholeheartedly in the traditional nerd pastime of quantifying and categorizing everything. I think that setting up concrete rules for intrinsically fluid concepts is probably harmful, both to the person setting the rules, and to the people they interact with. That said, Pedant Engines Engage! I’m going to try to define fun. I think that maybe fun and joy are different things. Joy you experience, but fun you participate in. You can pass through joy, letting it drape over you, but fun is something that you enact on the world. Now I’m really in it. Just when you thought I couldn’t get more up my own butt, I’m going to tell you what I think is going on in your head when you have fun. You can rest assured that I am not a psychologist, and have done little to no scientific research on this. That’s how you know this is really grade A choice cut pedantry. Fun is identifying patterns. That’s it. Nothing more to it. When we identify a pattern in what previously seemed like random noise, that experience, that feeling, that is what we call fun. The tiny rush you feel when you correctly predict the trajectory of a ball, move your hand to the right place at the right time and catch it mid flight. That might seem like very basic, predetermined mathematics. The ball will always follow this precise arc, over this precise distance, but the real world is lousy with variables. Is the wind blowing? How hard and in what direction? Is the ground even where you will place your foot? Are the aerodynamics of the ball consistent, or have they altered subtly? A few millimeters off in your prediction is the difference between a caught ball and a dropped one. Or maybe a broken nose. If you oscillate between unknowable chaos and recognizable, predictable patterns repeatedly, you have the formula for every sport ever played. Fun is a temporary, percussive sensation, but fun sustained can create joy. Nice theory, but what does that have to do with the Wonderful Waterful Robot? When anyone picked up that simple puzzle toy, they could never stop at pressing the button just once or twice. They would squeeze water through that thing again and again, varying the rhythm and power of each button press until they could get those 4 robot pieces to drift in just the way they wanted. Even releasing the button would cause some controllable turbulence. Soon the player would be able to select the piece they wanted to move and subtly direct its motion with deft control of the toys single button. The player began to predict the effect of forces that they could not see, on objects too diverse in size and shape to easily compute. Wonderful Waterful Robot is as pure an example of the human ability to find patterns in chaos as I have ever seen. It was simple and precise in a way that I doubt the creators had intended. People would pick it up, and spend several minutes fiddling with it, not because it was such a clever puzzle, but because it was fun.

0 Comments

This week I was doing some physics fiddling. Even early on in a game prototype, when I should be throwing everything at the wall, I tend to hold back. I’m always looking for that one thing that I implement that will push the entire flaming mess over the edge and reduce the framerate to Muybridge reference book. Of course, whatever that one thing was, it would be absolutely integral to the game and I would have to rebuild the entire structure from scratch just to work around it.

That never actually happens. It turns out that even the tiny computers in phones and tablets are ridiculously powerful, and it would take some truly thoughtless design to stop them from running most game prototypes. At one point I had it so that the game would get stuck in a loop and infinitely spawn physics objects that would collide with other physics objects triggering the spawning of even more physics objects. I left this mess running on my phone for several minutes. Eventually the game was drawing one frame every few seconds, but it never crashed. Most of the screen was filled with barely moving spheres, several hundred thousand pixel shaded polygons all told, each object with it’s own calculated physical reaction to the objects around it. I had made little to no attempt to optimise anything in the game, and still it kept on running. I used to test out new video cards by creating an array of duplicate primitive objects, cubes, spheres, or cones, in Maya. Early GeForce cards and Pentium2 processors could deal with a few hundred. The last time I tried that particular benchmark the fan on my Graphics card spun up, but the screen was filled with a 3D grid of objects that looked like a scifi novel cover. Cones as far as you could see in any direction. I haven’t tried it, but I suspect that my phone would perform pretty well in such a test. There is a reason why the digital special effects in Jurassic Park and Terminator 2 don’t look like “bad cg”. A lot of people, casual moviegoers and filmmakers alike, tend to say that it is due to the mix of practical, in camera effects, and computer generated effects. The real world puppets, makeup, and motion controlled models cover for the CG, because CG is always bad. This is, of course, completely wrong. These movies were made in the early days of digital effects. No one really knew what would work on film. Could a completely digital T-Rex command the same presence on screen as a real physical object would. Absolutely no one had an answer for that question, so the best course of action was to use the bleeding edge of technology as sparingly as possible. You could always cut around it if it didn’t work out. These new visual effects technologies were pushed only far enough to achieve the required effect on screen, and no more. Leaning on the liquid metal effect in Terminator 2 would mean that there would be no way to drop scenes that didn’t work. The end goal of the effects in T2 was the visceral feeling of battling an opponent without substance, it was never meant to be a catch all solution for every special effects need. The new film Mad Max Fury Road is applauded for it’s use of practical effects over digital ones. Barely a frame of that movie goes by without some digital manipulation. The color in every shot is bent so hard it could have been filmed in black and white and tones painted in after the fact. The effects never draw that much attention to themselves, because they are only used to achieve a certain feeling, they are not the content of the scene. With the staggering amount of processing power available to modern video games, it might seem possible to just turn on pretty shaders and dynamic physics and have that be your game. This is where, maybe some restraint is in order. If an processor intensive task is actually creating the feeling you want your players to be feeling it might be worth pursuing. If it’s not, but the technology is letting you get away with extras, it might be better to simply cut that effect and work around it. I have been using Playmaker a lot recently. Playmaker is finite state machine and visual scripting editor for unity. I like it a ton.

A finite state machine is a sort of burly flowchart. Rather than have simple yes/no options at the intersection of the flowchart, you have states that a program can be in. If you were creating a character movement system for a game you could have a state that waits for player input. Input would trigger another state where the character would move based on that input. There can be another state also running that would watch for collisions and transition the character out of movement and into a collision animation when they hit a wall. States can be one shot effects, that terminate on completion or transition back to a previous state, or they can be loops that run continuously until some criteria is met triggering a transition. There are probably as many ways to wire these states up as there are people who look at the problem. While not all programming problems can or should be solved using finite state machines, they are ridiculously powerful tools. They are especially useful for videogames because games by their nature are interactive and reactive computer programs. Input produces output, and everything is based on interlocking systems and rules. Playmaker is also a visual scripting tool. One of the main selling points for visual scripting is that you don’t need to know a programming language to use it. Most tasks in a visual editor are drag and drop, click buttons, and fill in input field operations. Of course, not needing to know a programming language is a long ways from not knowing how to program. Playmaker can streamline the process a bit, but you won’t get much out of it until you can plan out a logical sequence of events. If you have some experience with any programming language you will have a much easier time navigating Playmaker. C# happens to be the language that Playmaker is written in so that might be a good place to start. Then again, I started with z80 basic, so what do I know. Of course a lot of people come to these visual scripting tools with no programming knowledge at all. Without context it may be more difficult to figure out what’s going on in Playmaker, but I think this is where these types of tools really shine. I feel relatively comfortable shifting back and forth between Playmaker and C# scripts in the “knows just enough to be dangerous” sort of way, but I could imagine someone transitioning smoothly from learning a visual scripting tool to learning plain old, no tool assisted, programming. In fact, I think this will be the preferred way to teach programming to kids until we can come up with something better. For the project I’m currently working on, I plan to use Playmaker as much as possible. Occasionally that has meant writing a quick addon script for it in C# just so I could do something that was difficult or cumbersome inside the visual tool. Keeping all my game logic in the state machine framework of Playmaker is also incredibly useful. Crimsonland

vast flat empty waste fertilized with care and blood only danger grows |

Archives

February 2024

Categories |

Owen McManus

RSS Feed

RSS Feed